All Activity

- Today

-

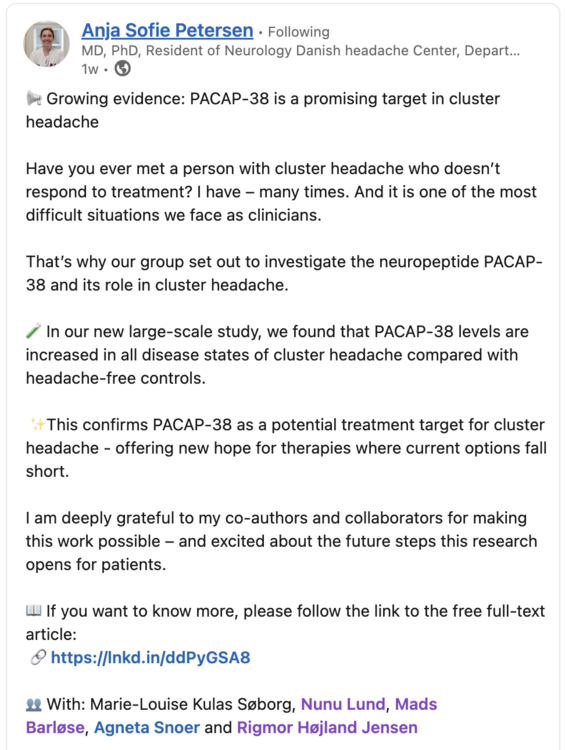

I’d like to offer a contemporary perspective on recent patient reports from the cluster headache (CH) community alongside my own experience regarding the treatment of CH with nutritional interventions. This draws on a range of emerging research to explore how modulation of the gut microbiota more so than any one diet may present as a novel future therapeutic target in CH. As best I can as a CH patient, I will attempt to integrate the converging lines of evidence that support this hypothesis including a case report, drawn from the grey literature, illustrating the clinical application of such a targeted microbiome-based approach and conclude with some final thoughts on what really is a fascinating subject. More bacteria than we are human... The human genome encodes for between 20,000 and 25,000 genes. In remarkable comparison our collective microbial genome, comprised of trillions of microbes that inhabit our bodies, contains an estimated 3,000,000 to 4,000,000 million genes. The gut microbiota is a vast community of bacteria, fungi, viruses and archaea that inhabit the gastrointestinal tract, with the highest density of microbes anywhere in the body found in the colon. The diversity of this community is influenced by a number of factors including diet, environment, motility, autonomic tone, antibiotic exposure, previous infection, vitamin D3 and psychedelics (more on the vitamin D3 and psychedelics later). Their primary energy source is dietary fibre and other non-digestible carbohydrates of which they ferment into short-chain fatty acids (SCFA’s) such as acetate, propionate and butyrate. They also synthesize vitamins such as vitamin K and several B-group vitamins, amino acid derivatives like indole and GABA and secondary bile acids that in turn regulate metabolism and immune function. Together these microbes and their metabolites play an existential role in maintaining gut integrity, modulating inflammation and supporting our overall health. Balance is the key to life... that sentiment resonates with me... When this community of microbes is balanced, or in eubiosis, the relationship is mutually beneficial. We nourish the microbes and they nourish us. When the balance of this community is disrupted, disease may follow through a process referred to as dysbiosis. Imbalance of the microbiota may degrade the mucin layer, a protective layer of mucous that protects the epithelial lining of the gut. When the mucosal layer is degraded, disruption may occur at the level of the epithelium where the tight junctions that maintain integrity of permeable membranes are compromised, increasing the translocation of toxins from the gut into blood and lymph where they invoke an immune response. An example of this is lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a structural component of the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria. LPS engages the toll like receptor 4 (TLR4) complex on innate immune cells, activating the transcription factor nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), which translocates to the nucleus and upregulates the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). This cascade contributes to a process commonly referred to as “leaky gut” syndrome. Emerging Migraine Research... Whilst CH and migraine are clinically distinct disorders they do share several overlapping mechanisms including activation of the trigeminovascular system and neurogenic inflammation, as well as responsiveness to medications such as triptans and anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies such as Emgality. Both conditions also exhibit cyclical patterns and hypersensitivity within pain processing networks. Given the larger body of research on migraine, it is useful to cautiously draw insights from migraine studies given they may reveal potential pathophysiological processes and therapeutic targets relevant to CH. In my view recent literature seems to have shifted the understanding of migraine from a neurovascular disorder toward a systemic inflammatory condition modulated by the gut-brain-immune axis. Multiple independent studies now converge on the idea that gut dysbiosis and intestinal permeability are central to migraine pathophysiology. A study by He et al. (2023) confirmed a causal relationship between gut microbial composition and migraine risk, identifying protective taxa such as Bifidobacteriales and pathogenic associations with Anaerotruncus and Clostridium genera, providing what I believe was the first robust evidence that microbiota composition can directly influence migraine susceptibility. In a 2024 study, Vuralli et al. found elevated serum LPS, VE-cadherin, HMGB1 and IL-6 in chronic migraine patients with medication overuse, supporting a “leaky-gut” inflammatory phenotype linked to trigeminal sensitization. Recent reviews and meta-analyses converge on much the same theme; migraineurs show lower microbial diversity, depletion of SCFA producing species such as Faecalibacterium and Roseburia and a relative overgrowth of pro-inflammatory species. Emerging clinical research supports therapeutic modulation of the microbiota. Grodzka and Domitrz (2025) conducted a meta-analysis that showed probiotic supplementation reduced migraine frequency with mixed effects on severity whilst Kappéter et al. (2023) proposed fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) as a means of microbial restoration and normalizing the inflammatory mediators implicated in migraine chronification. What does the CH literature say? Comparable findings in CH are absent however new evidence does show an emerging persistent inflammatory signature. In peripheral blood, Lund et al. (2025) found distinct cytokine profiles across all CH types with oncostatin M (OSM), an IL-6 family cytokine, elevated in cCH, eCH in-cycle and eCH in remission groups. In cerebrospinal fluid, Ran et al. (2024) demonstrated higher chemokine concentrations with a serum-to-CSF gradient, concentrating inflammation within the central nervous system (CNS) and present both during active cycle and remission periods. More recently, PACAP-38 has also been found to be elevated in CH compared with controls, further supporting the presence of sustained neuroimmune activation involving vasoactive peptides even during remission periods. And whilst an underlying inflammatory signature has now been identified, the upstream driver of these elevated markers remains unlinked to dysbiosis. Taken together however these new findings point to CH as a condition underpinned by ongoing inflammation within the CNS rather than a series of isolated pain events attributed to dysfunction of the hypothalamus. So, what was this about a diet? Sign me up! What has recently been referenced by myself and others in the CH community is a 2018 case-control study by Di Lorenzo et al. that examined the effects of a ketogenic diet in a small cohort of 18 chronic CH patients refractory to standard preventive treatments. The authors reported that 15 participants responded favorably, with 11 achieving sustained pain-free remission and 12 choosing to remain on the intervention even after the study concluded. Although the mechanism of action was not explored, it is my view that the therapeutic benefit of the ketogenic diet likely extends beyond the metabolic effects of ketone production to include modulation of the gut microbiota and its associated inflammatory milieu. To my knowledge, this remains the only dietary intervention in CH and while the sample size was small the findings were nonetheless remarkable. Here warrior – I recommend giving this a try... Consider this a brief pause, a half-time reflection, before moving into the following sections. Few examples illustrate the power of patient-led initiatives better than what the CH community has been able to achieve. Out of necessity and sheer persistence, patients have effectively conducted some of the most successful citizen science projects in existence. From the early work exploring psychedelic therapy to the development of the vitamin D3 anti-inflammatory regimen, each step has been driven by individuals determined to find solutions where few existed. These remarkable efforts have produced measurable results and practical treatment tools that continue to change the lives of CH patients, indeed not all heroes wear capes. Where vitamin D3 & psilocybin converge... What I find particularly intriguing is that both of these therapies, psychedelic compounds and the Vitamin D regimen, according to emerging research, may exert part of their therapeutic effect through interactions with the gut microbiota. At the same time, their variable efficacy from one CH patient to another may be influenced by the baseline state and diversity of that patient’s microbiome. This bidirectional relationship, in which treatment both shapes and is shaped by its interaction with the microbiota, may help explain why some experience complete remission while others achieve only partial or temporary relief, or require higher or repeated doses. In the following sections, I will examine the literature that highlights the potential points of convergence between Vitamin D and psilocybin, focusing on microbiome mediated interactions. Oh vitamin D3, you have been kind to me... For almost a decade now, the Vitamin D3 anti-inflammatory regimen has kept me mostly pain-free from CH. Beyond its role in calcium homeostasis Vitamin D3 plays a key role in maintaining gastrointestinal homeostasis. The active form, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, binds to the Vitamin D receptor (VDR), which is expressed throughout the intestinal epithelium and immune cells. Through this signaling pathway Vitamin D3 influences epithelial integrity, microbial diversity and modulates the immune response (Vemulapalli et al., 2025). In refining the original regimen, Pete Batcheller included a B-complex, taking inspiration from Gominak’s work linking Vitamin D restoration to improved sleep and gut function through the microbiota’s production of B vitamins (Gominak, 2016). Gominak proposes that both Vitamin D and the microbiota exist in a symbiotic relationship, where Vitamin D supports the host environment necessary for microbial balance while a healthy microbiota contributes to the production of essential cofactors necessary for neuronal and immune health. Charoennngam et al. (2020) demonstrated that Vitamin D3 supplementation shifts the microbiota toward a less inflammatory profile, increasing beneficial commensal species such as Bacteroides while reducing pathogenic species like Porphyromonas. In regards to maintenance of the epithelial membranes, Vitamin D3 upregulates tight-junction proteins such as claudins and occludins while lowering zonulin expression, a key marker for intestinal permeability. By strengthening tight junctions Vitamin D3 may limit translocation of bacterial endotoxins such as LPS into systemic circulation (Fedele et al., 2018; Stio et al., 2016). In addition to maintaining gut barrier integrity, Vitamin D3 modulates the immune response by inhibiting NF-κB activation and reducing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines while supporting T regulatory cell function and the production of antimicrobial peptides such as cathelicidins and beta defensins (Vemulapalli et al., 2025). Taken together these findings place Vitamin D3 as a key mediator in gut-immune homeostasis, acting at the bleeding edge between the microbial landscape and host defense. Importantly, as demonstrated by Holick and colleagues in Scientific Reports (2019), the genomic actions of Vitamin D3 are dose and blood-level responsive with higher 25-hydroxy vitamin D levels resulting in broader transcriptional changes across hundreds of genes involved in immune regulation. The fact that Pete Batcheller’s regimen has been assembled into a simple and accessible protocol with consistently impressive response rates is in itself a remarkable achievement given the devastating nature of CH. Whilst Vitamin D3 almost certainly acts on receptors within the trigeminal ganglion and hypothalamus, these recent findings suggest its actions in the periphery, particularly within the gut, may play an important role in the therapeutic efficacy of the anti-inflammatory regimen. What can mushrooms possibly have to do with any of this? Intriguing new research suggests that the therapeutic effects of psychedelics, particularly psilocybin, may in part be mediated through interactions with the gut microbiota. While its best described actions involve modulation via the serotonergic receptor, new findings reveal that psilocybin also exerts systemic effects on inflammation, immune signaling, intestinal barrier integrity as well as shaping the microbial landscape itself. Wang et al. (2025) provide an elegant synthesis of this evolving concept in a recent ACS Chemical Neuroscience viewpoint, suggesting that the therapeutic effects of psychedelics including psilocybin extend beyond cortical serotonergic circuits to modulate the gut-brain axis via interactions with the microbiome. Building on emerging evidence they position these compounds as both neuroactive and immunomodulatory agents, potentially influencing inflammation along the microbiota-gut-brain pathway via NF-κB mediated cytokine modulation as shown in complementary models like Zanikov et al., 2024. Zanikov et al. (2024) were able to show in a mouse model of colitis that psilocybin reduced gut driven neuroinflammation and lowered the expression of inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6 and COX-2 in brain parenchyma. These findings link intestinal inflammation directly to a central inflammatory response and confirm that psilocybin’s anti-inflammatory effects occur along the gut-brain axis rather than within the brain alone. Complementary in vitro work in human macrophages shows dose dependent suppression of LPS induced cytokines via modulation of NF-κB signaling, highlighting its broad immunoregulatory potential. Kelly et al. (2023) introduced the term “psilocybiome” as a framework to describe the bidirectional relationship between psychedelics and the microbiota-gut-brain axis, they propose that microbial diversity and metabolism influence every phase of psychedelic therapy from preparation and acute experience to integration. Caspani et al. (2024) build on this by exploring psychedelics potential antimicrobial effects and how they may reshape gut ecology, suggesting that microbial composition modulates psychedelic pharmacokinetics while remarkably, psychedelics, in turn, remodel the microbiota. This research suggests that psilocybin’s therapeutic benefit may indeed depend on the baseline composition and inflammatory state of the gut microbiome. This perspective offers a fresh view for the variability in dose response observed within the CH community’s collective busting experiences. It appears reasonable to suspect that interventions which restore microbial balance and support gut integrity may enhance the therapeutic window for psychedelic therapy. Although the degree to which these microbial mediated mechanisms contribute to the therapeutic benefit we see in busting for CH remains speculative, these new findings make clear that psilocybin’s actions reach beyond the mind, extending into the intricate microbial terrain in a complex dance that is beginning to be revealed. So what about that case report? Recent clinical evidence provides an example of how restoring microbial homeostasis may be achieved through an integrative approach. A 2023 case report by Beltran and Guimarães described the successful treatment of a patient with psoriasis vulgaris refractory to conventional therapies using a combined anti-inflammatory diet, high-dose vitamin D3 therapy and targeted herbal antimicrobials. The case report used a diagnostic workup that included the Gastrointestinal Microbial Assay Plus (GI-MAP), a DNA-based stool test that identifies bacterial, fungal and parasitic taxa as well as markers of gut inflammation and intestinal permeability by Quantitative PCR (qPCR). This diagnostic framework provided a precision-based view of the patient’s baseline microbial state and guided subsequent therapeutic choices. Such testing reveals that, just as no two microbiomes are identical, one size may not fit all in nutritional or supplement interventions. Importantly, dysbiosis patterns and their immunological signatures vary between individuals which necessitates personalized modulation of the microbiota rather than blanket probiotic or dietary advice. In the specific case testing revealed small intestinal fungal overgrowth (SIFO) driven by Candida albicans. These results informed a selection of herbal antimicrobials, notably oregano oil for its antifungal and biofilm-disruptive properties. Oregano oil’s mechanisms include membrane disruption and inhibition of fungal enzyme activity which reduce microbial burden and help restore mucosal homeostasis. To complement this, Curcumin longa (turmeric) was used for its capacity to inhibit NF-κB-mediated inflammation and upregulate VDR expression in epithelial and immune cells. Following five months of intervention immunofluorescence analysis of VDR expression in skin biopsies revealed upregulation of receptor density compared with baseline, correlating in full clinical remission. This finding parallels the discussion advanced in Beltran’s companion paper, Vitamin D Receptor Renewal Through Anti-Inflammatory Diet, which identifies the suppression of VDR by LPS, mycotoxins and inflammatory cytokines as key drivers of vitamin D resistance in chronic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. By resolving dysbiosis and improving epithelial integrity through diet, the intervention removed the upstream inflammatory blockade to VDR transcription and restored immune tolerance. Where and how to even conclude this...? Cluster headache, long regarded as the most devastating disorder, may find part of its explanation not in the brain alone but in the microbial world that indeed sustains it. As our understanding of the gut-brain-immune axis deepens, the concept that dysbiosis and intestinal permeability may act as upstream drivers of neuroinflammation becomes increasingly difficult to ignore. While the literature in CH remains in its infancy, speculative bridges are clearly already being built with patents having been filed for microbial modulating technologies aimed at treating headache disorders, such as US9987224B2, which describes methods for altering gut microbiota composition to influence neurological outcomes including migraine and CH. Such developments are another signal of the growing recognition that modulating our microbial landscape presents as an attractive therapeutic target for disorders once considered purely neurogenic in origin. All being said, it's early days – what I think we have is an interesting hypothesis more so than settled science for CH specifically. The ketogenic results are impressive but need larger, controlled trials; vitamin D3 works for many but the anti-inflammatory regimen remains without clinical validation in CH and psilocybin's ties to the microbiome are certainly intriguing but mostly preclinical. All three treatment options are available for patients to pursue at their own discretion. I hope I have been able to articulate my take on the current literature and of course welcome your thoughts, comments and ideas. I have tried to be as accurate as possible, please point out any shortcomings. Many questions remain covering other important topics in CH such as genetics, periodicity and the role of personality; still – I feel like it is an exciting and hopeful time and look forward to seeing what future research may show in regards CH and the microbiome. References Migraine Vuralli, D., Akgör, M.C., Gök Dağıdır, H. et al. (2024) ‘Lipopolysaccharide, VE-cadherin, HMGB1 and HIF-1α are elevated in chronic migraine with MOH: evidence of leaky gut/inflammation’, J Headache Pain. Link: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10875763/ He, Q., Zhang, Y. and Li, R. (2023) ‘A causal effects of gut microbiota in the development of migraine’, J Headache Pain. Link: https://thejournalofheadacheandpain.biomedcentral.com/... Grodzka, O. and Domitrz, I. (2025) ‘Gut microbiota, probiotics, and migraine: a clinical review and meta-analysis’, Journal of Oral & Facial Pain and Headache. Link (journal): https://www.jofph.com/articles/10.22514/jofph.2025.043 Kappéter, Á., Zając, A., Domitrz, I. (2023) ‘Migraine as a disease associated with dysbiosis and possible therapy with fecal microbiota transplantation’, Biomedicines. Link: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10458656/ Cluster Headache Lund, N.L.T., Pedersen, S.H., Ashina, M. et al. (2025) ‘Distinct alterations of inflammatory biomarkers in cluster headache: a case–control study’, Annals of Neurology. Link (journal): https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ana.27205 Ran, C., Yang, Y., Guo, S. et al. (2024) ‘Elevated cytokine levels in the central nervous system of patients with cluster headache’, J Headache Pain. Link: https://thejournalofheadacheandpain.biomedcentral.com/... Søborg, M.L.K., Amin, F.M., Ashina, M. et al. (2025) ‘PACAP-38 in cluster headache: a prospective, case-control study of a potential treatment target’, Eur J Neurol. Link (PubMed): https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/41002104/ Ketogenic Diet Di Lorenzo, C., Coppola, G., Sirianni, G. et al. (2018) ‘Efficacy of Modified Atkins Ketogenic Diet in Chronic Cluster Headache: An Open-Label, Single-Arm Clinical Trial’, Frontiers in Neurology. Link: https://www.frontiersin.org/.../10.../fneur.2018.00064/full Vitamin D3 Vemulapalli, R., Thomas, A. (2025) ‘The Role of Vitamin D in Gastrointestinal Homeostasis and Gut Inflammation.’, Int. J. Molecular Sciences Link: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40243631/ Gominak, S.C. (2016) ‘Vitamin D deficiency changes the intestinal microbiome reducing B-vitamin production in the host: a hypothesis explaining chronic sleep disorder’, Medical Hypotheses. Link (PubMed): https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27515213/ Charoenngam, N., Shirvani, A., Holick, M.F. (2020) ‘The Effect of Various Doses of Oral Vitamin D3 Supplementation on Gut Microbiota in Healthy Adults: A Randomized, Double-blinded, Dose-response Study’, Anticancer Research. Link: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31892611/ Stio, M. et al. (2016) ‘Vitamin D regulates the tight-junction protein expression in active ulcerative colitis’, Scand J Gastroenterol. Link (PubMed): https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27207502/ Scricciolo A, Roncoroni L, Lombardo V,Ferretti F, Doneda L,Elli L (2018) ‘Vitamin D3 Versus Gliadin: A Battle to the Last Tight Junction’, Digestive Diseases and Sciences. Link: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29159680/ Shirvani A, Kalajian TA, Song A, Holick MF. (2019) ‘Disassociation of vitamin D’s calcemic and non-calcemic genomic activity & individual responsiveness: RCT’, Scientific Reports. Link: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-53864-1 Psychedelics Wang, X., Li, H. and Zhou, Z. (2025) ‘Psychedelics and the Gut Microbiome: Unraveling the Interplay and Therapeutic Implication’ (Viewpoint), ACS Chemical Neuroscience. Link (journal page): https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acschemneuro.5c00418 Zanikov, T., Gerasymchuk, M. and Robinson, G.I. (2024) ‘Psilocybin and eugenol prevent DSS-induced neuroinflammation in mice’, Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology. Link: https://www.sciencedirect.com/.../pii/S1878818124000161 Caspani et al. (2024) ‘Mind over matter: the microbial mindscapes of psychedelics and the gut-brain axis’, Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. Link: https://www.sciencedirect.com/.../pii/S1043661824002834 Kelly, J.R., and Clarke, G. (2023) ‘Seeking the Psilocybiome: Psychedelics meet the microbiota-gut-brain axis’, International Journal of Psychopharmacology Link: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9791138/ Case Report & Other Beltran, E.P. and Guimarães, G. (2023) ‘High-dose vitamin D3, anti-inflammatory diet and targeted antimicrobials in psoriasis vulgaris: clinical case with VDR immunofluorescence’, Zenodo case report (grey literature). Link: https://zenodo.org/record/7799594 Beltran, E.P. (2023) ‘Vitamin D Receptor Renewal Through Anti-inflammatory Diet’, ResearchGate/Institutional page (grey literature). Link: https://www.researchgate.net/.../369801068_Vitamin_D... US 9,987,224 B2 (2018) ‘Method and system for preventing migraine headaches, cluster headaches and dizziness.’ Link (Google Patents): https://patents.google.com/patent/US9987224B2/en

-

jluck8com joined the community

-

f168studio changed their profile photo

-

f168studio joined the community

-

23win06world joined the community

-

okviplienminhcom1 joined the community

-

mb66zacom joined the community

- Yesterday

-

Lionel Ortiz joined the community

-

luck8882makeup1 joined the community

-

mohitagarwal changed their profile photo

-

mohitagarwal joined the community

-

vipinsodia changed their profile photo

-

mohneeshgupta changed their profile photo

-

devendrakumarbabbar changed their profile photo

-

neerajchaudhary changed their profile photo

- Last week

-

REUBEN started following 2018 Conference Room Share Thread , Conference Room Share Thread and 2017 Conference Room Share Thread

-

dranjaligupta changed their profile photo

-

jun88casinotop changed their profile photo

-

13winarchi changed their profile photo

-

Not really a psychedelic, but I've been experimenting with Ketamine for both cluster headaches and migraines for nearly a year and had some very promising results. Check out my thread here if interested:

-

mm88csncom changed their profile photo

- Earlier

-

Hi CHfather - thanks for stopping in. This is the first case series I am aware of looking at a gepant and CH, in this case Qulipta / Atogepant. There is a trial looking at Nurtec / Rimegepant as a preventative therapy for CH. Ubrelvy / Ubrogepant is more an acute treatment owing to short half-life makes preventive use impractical and may not act quickly enough for acute CH attacks. I haven't read anything about the third generation gepant Zavegepant, again an acute treatment via nasal spray. I haven't really followed patient feedback on any them tbh. I think this case series, if anything, may provide some context for clinicians considering where to next for refractory CH patients non-responsive to other treatments, including anti-CGRP mAbs like Emgality / Galcanezumab - this suggests that atogepant may be worth a try. I imagine there may be a tendency to think if a mAb hasn't previously worked or stopped working as was the case for one of the cases, a gepant is unlikely to either. That being said, ya'll know I have had success with the vitamin D3 anti-inflammatory regimen and my personal view would be to exhaust the patient led treatments options that we have (busting + regimen) paired with abortives (oxygen and more recently DMT) before considering one of these new treatments because I am somewhat adverse to risk and there is no long term clinical data on their safety. For refractory patients for whom my heart truly aches, this may offer some hope - still, an early signal and a small case series.

-

Interesting, thanks for posting this. My Neuro has prescribed this for me at 60mg. I’ve not started just yet as I’ve been having some success with busting with 5-MeoDalt. Down to 1 attack per week and low pain shadows between. I was considering adding this layer on top. The cgrp blocker side effects of constipation and hair shedding give me the fear also :/

-

We have such an amazing community and it's hard to just pick a few people, so for our 20th we picked a few extra But seriously we have the best community- just wanted to give a shout out to these amazing people!

-

- 1

-

-

Vagus Nerve Stimulation Webinar

eagleswings replied to eagleswings's topic in Advocacy, Events and Conferences

The recording is on our YouTube channel if you'd like to watch.- 1 reply

-

- 1

-

-

Here is a screenshot from one of the authors posts on LinkedIn. The research coming out of the Danish Headache Center is outstanding, I have recently shared the findings of their paper identifying the distinct cytokine profiles that distinguish eCH from cCH and also found that Oncostatin M was elevated in all 3 CH states.

- 1 reply

-

- 1

-

-

PACAP-38 in Cluster Headache: A Prospective, Case–Control Study of a Potential Treatment Target Marie-Louise K. Søborg, Nunu Lund, Agneta Snoer, Mads Barloese, Rigmor Højland Jensen, Anja Sofie Petersen Published in European Journal of Neurology on September 26, 2025 Link: https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.70341 Abstract: (partial selection) This large-scale study demonstrated increased PACAP-38 levels in all disease states of cluster headache compared to headache-free controls, strengthening the hope of a possible effect of PACAP-38 targeting treatments in future trials. The lacking correlation between PACAP-38 and CGRP levels should be interpreted with caution and needs to be investigated in future studies.

- 1 reply

-

- 1

-

-

In the US, the brand name for atogepant is Qulipta. In the EU, I think it's Aquipta. @Craigo, thank you for this (and for all your other great contributions to substantive knowledge about CH)! I notice that Ubrelvy and Nurtec are both also gepant formulations. Might we imagine that they would also help (it seems from the abstract that the contrast in this study is with galcanezumab (Emgality))?

-

Can atogepant be a preventive treatment for cluster headache?-Insights from a case series Catarina Serrão, Filipa Dourado Sotero, Linda Azevedo Kaupilla, Isabel Pavão Martins Published in Headache on October 3, 2025 Link: https://doi.org/10.1111/head.15066 Abstract: Cluster headache (CH) is a disabling primary headache disorder with limited therapeutic options. Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) is known to be involved in CH pathophysiology; however, except for galcanezumab (300 mg) in episodic CH, anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies did not reduce CH attacks in randomized clinical trials. Atogepant is an oral, small-molecule, CGRP receptor antagonist, which is approved for the preventive treatment of migraine. Here, we describe four case reports of CH (two episodic CH and two chronic CH), unresponsive to previous prophylactic treatments, who responded to daily atogepant (60 mg). Chronic CH cases were refractory to subcutaneous galcanezumab. In one case, a reduction to atogepant (30 mg daily) resulted in recurrence of headache attacks, which subsided on reintroduction of the initial dose. No serious adverse effects were reported. Despite the limited number of cases and the open retrospective design, our case series suggests atogepant as a possible prophylactic treatment for CH. Further research on CGRP signaling in CH and the implementation of well-designed clinical trials are necessary.

-

Responsive Respiratory 120-1230 EMS CGA 870 Regulator 25 LPM with Dual DISS and Barb – Broward A&C Medical Supply

-

CGA 870 for E-tanks. On same link as Racer posted.

-

TUESDAY NIGHT October 7 at 7pm ET During the session, you’ll: ● Understand how gammaCore works to treat cluster headache, including the science behind vagus nerve stimulation and its role in regulating pain signals. ● Learn strategies for incorporating gammaCore into your care plan and understand when and how to use it effectively. ● Have the opportunity to ask questions during a live Q&A session. Register Now: https://us06web.zoom.us/meeting/register/SrvzB0d4RoiK4Dz8ITjvrQ

- 1 reply

-

- 1

-

-

If you have significant pain all day, and the attacks that seem like CH are "bursts" as you write (which I think of as briefer than a typical CH attack), and if a triptan doesn't help, it seems possible to me that you might have one of the CH "lookalikes," some form of hemicrania, maybe paroxysmal hemicrania (Paroxysmal Hemicrania: Causes, Symptoms & Treatment) or hemicrania continua (Hemicrania Continua: Causes, Symptoms & Treatment). I'm just guessing here: you can look to see how well the symptoms match. Unlike CH, hemicrania is generally not responsive to triptans or oxygen (or busting, except for some brief relief of maybe a day or two). So one test would be to take the medicine that treats hemicrania, Indomethacin. Another would be to try oxygen. As I say, I'm just guessing here. Sometimes people "try" Indomethacin, but the dosage isn't enough, or it's not continued long enough, to get a real test. This is the recommendation from the International Headache Society: "In an adult, oral indomethacin should be used initially in a dose of at least 150 mg daily and increased if necessary up to 225 mg daily. The dose by injection is 100-200 mg. Smaller maintenance doses are often employed."

-

Wow, that's terrible, sorry to hear it! If your neuro wasn't a headache specialist, well those are the ideal ones you want to see - it can be quite the long wait to get an appointment with one though, and that seems pretty universal, no matter what country you reside in. Last I checked, verapamil is known for lowering blood pressure, and is even prescribed for treating high blood pressure, so I wouldn't imagine your high blood pressure to be a verapamil side effect. I'll leave the T syndrome (or did they test for "T series"?) abnormality for others who may know about it. Sumatriptan injections have historically been prescribed in too high of a dose, specifically 6 mg, whereas doses of 3 mg (or even 2 mg for those such as myself), are plenty effective at aborting cluster attacks if caught at onset. It could be worthwhile to let us know what kinda sumatriptan and verapamil doses you have been prescribed - if you've been issued the big dose 6mg Sumatriptan (which I would have to think would increase risk of side effects), there are ways to split those injections:

-

So sorry to just be coming for advice again rather than actually offering anything but it's been a horrendous couple of weeks. I was kept in hospital for a couple of nights after the last post but did get a CT scan which was clear, saw a neurologist who referred me for an MRI. Had that on Sunday, which was very quick for the NHS. He also prescribed verapamil and sumatriptan injections on discharge although he's not convinced about a cluster headache diagnosis because of my age. Things had been slightly better - not great but I've been functioning. Today's been awful though, I've got immense pressure in my head all the time that won't ease as well as the cluster headache symptoms. I went for an ECG yesterday to check that I was OK to continue with verapamil - at my GPs who are never great - and after checking my notes it says I have a T syndrome abnormality - has anyone had that before and were you able to continue with verapamil. My blood pressure was also much higher than normal. None of which was discussed with me but that's par for the course to be honest. I've also started having a weird reaction to the Sumatriptan injections - the pain moved all over my head but its really immense and not like any reaction I've ever had to triptans before - should that be worrying me? In between that the pain flare ups still feel like cluster headaches - it's definitely my trigeminal nerve. Any advice would be appreciated because I'm a bit scared and lost at the moment

-

ABSTRACT: Classic psychedelics and the gut microbiome interact bidirectionally through mechanisms involving 5-HT2A receptor signaling, neuroplasticity, and microbial metabolism. This viewpoint highlights how psychedelics may reshape microbiota and how microbes influence psychedelic efficacy, proposing microbiome-informed strategies such as probiotics or dietary interventions to personalize and enhance psychedelic-based mental health therapies. Psychedelics and the Gut Microbiome: Unraveling the Interplay and Therapeutic Implications https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acschemneuro.5c00418 A fascinating new view-piece synthesizing the current literature exploring psychedelic / gut / microbiome interaction in the context of depression. Wang and colleagues emphasise that "the baseline composition and functional state of the microbiome can shape psychedelic pharmacology and therapeutic efficacy, while the psychedelic experience itself can remodel the gut microbiome in ways that influence ongoing physiological and psychological adaptation." At the cellular level they note psychedelics suppress the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α through 5-HT2A receptor-mediated inhibition of NF-κB signalling: "this immunomodulatory action establishes an anti-inflammatory milieu that favors the growth of beneficial commensal bacteria." Compounds such as psilocybin and DMT "reduce pro-inflammatory cytokine expression and enhance epithelial barrier integrity, promoting the expansion of anti-inflammatory taxa." They note, the microbiome is not a passive bystander: "gut bacteria express a variety of enzymes capable of biotransforming these substances, thereby shaping their pharmacokinetic profiles. For instance, Bifidobacterium species have been shown to affect the metabolism of DMT, potentially altering the intensity and duration of ayahuasca experiences. Similarly, in vitro studies have identified bacterial strains that dephosphorylate psilocybin into its active form, psilocin, suggesting that individual differences in microbiota composition may underlie variability in therapeutic response." Wang et al. refer early human data noting that "although human studies remain limited, early observations suggest that psychedelic treatment may be associated with alterations in fecal microbial diversity in patients with depression." These observations support what the authors call a "systems-level perspective of psychedelic therapy - one that encompasses not only neural targets but also immunological, endocrine, and microbial domains." The article is behind a paywall, send me a message if you'd like a copy of the article. For more reading the article cites this paper "Seeking the Psilocybiome: Psychedelics meet the microbiota-gut-brain axis" https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9791138/ In the context of CH, with new evidence of persistent immune-inflammatory activity suggests psychedelic therapy not as acting solely on the brain but by potentially intersecting with the upstream gut-barrier-immune processes that maintain systemic inflammation that are now attributed as a causative agent in migraine. The paper also goes some way to positing a possible reason for the variations we see in busting efficacy. This area of research is fascinating and I think the piece provides a further and new angle as to the role gut health may play in CH alongside recent findings in migraine although there is much road to travel before we have any concrete evidence of this. Still mulling my thoughts, all I offer here is a view - always interested in yours. With respect, Craig.

-

- 2

-

-

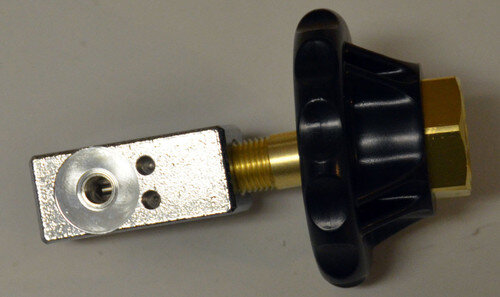

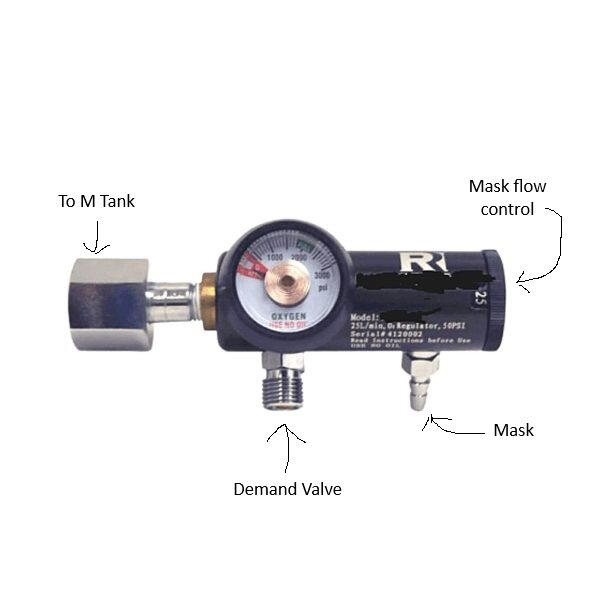

One of the issues we as CH O2 users has been when we have both M and E tanks available to use. The M/Welding tanks use a CGA540 connection, and the E tanks use a CGA870 thus preventing swapping regulators between the two. While I've known of an adaptor that allows you to run M tank regs on E tanks, I've only heard talk of a device that allows to reverse, the ability to use a E tank reg on a M tank. Until now, I didn't think such an adaptor could be sourced, but I finally found it and have tested it myself. It works!! There is a nonstandard seal requirement, but that's easily met. You simply order the thick seals linked below and use them in place of the standard brass/rubber seals we normally use. I have no financial connection to these items, and this is for informational purposes only. You be the judge if this set up is right for you. The adaptor. The seals.

-

- 2

-

-

Hi all. I wanted to build on a post couple of months back that mentioned this early 2025 study in Annals of Neurology which found that Oncostatin M (OSM) was significantly elevated across all forms of cluster headache (CH), episodic in cycle (ECH), episodic in remission and chronic (CCH) when compared with controls. Distinct Alterations of Inflammatory Biomarkers in Cluster Headache Lund, N. L. T. et al. Annals of Neurology. 2025 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39981939/ Interpretation: Findings show that the immune system is altered in all 3 states of cluster headache compared with controls. Oncostatin m was elevated, constituting a promising target for future studies. The distinct alterations between episodic and chronic cluster headache are striking and urges further research of the immune system in cluster headache to better understand its potential role in prediction of disease activity and treatment response. OSM belongs to the interleukin-6 family of cytokines which are signalling molecules released by cells to facilitate communication within the immune system and the body, acting as messengers and binding to receptors on other cells to trigger responses like inflammation, cell growth and immune cell activation. OSM is produced mostly by activated monocytes and macrophages along with T-cells once the immune system is already engaged. Triggers include microbial products such as lipopolysaccharide acting on toll-like receptors, upstream cytokines like IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 as well as T-cell activation itself. In other words OSM typically appears as a second-wave signal once innate and adaptive cues are already active. After its release OSM signals through receptor complexes that require gp130 subunit, a shared hub for the IL-6 family. OSM pairs gp130 with either OSMR or LIFR receptors which activate Janus kinase enzymes (JAKs). JAKs phosphorylate STAT3 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 3) and activated STAT3 then enters the nucleus to upregulate genes for chemokines, adhesion molecules and matrix metalloproteinases. Short-term controlled activation of this pathway is essential for tissue repair but sustained persistent activation may lead to detrimental effects including weakened barriers, leukocyte recruitment and ongoing systemic inflammation. In Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis OSM has been shown to drive stromal activation and barrier dysfunction and high levels of OSM are a predictor of poor response to anti-TNF-α therapies. The CH study by Lund and colleagues suggests a similar kind of hard-to-quiet inflammatory program in the cranial milieu of CH patients regardless of whether or not they are in active cycle. So what may drive the persistent upstream activation that induces OSM in the first place? This wasn't discussed in the article but one source that may deserve attention is the emerging gut-immune-brain axis. As explored in my earlier post, a growing body of literature in migraine describes altered gut and oral microbiota, reduced microbial diversity, links to markers of intestinal hyperpermeability and bacterial endotoxin exposure as causative agents in migraine pathology. While migraine and CH are distinct disorders both share neuroinflammatory components, cytokine involvement and respond to many of the same treatments, is it reasonable to ask whether dysbiosis may help maintain the triggers that induce OSM expression? And if so what implication does that have on future treatment strategies for CH? And where might the Vitamin D regimen fit into this picture? The active form of Vitamin D, calcitriol, binds to the vitamin D receptor in immune and barrier cells and influences the expression of hundreds of genes. It suppresses NF-κB and MAPK signalling, promotes regulatory T-cells and IL-10 and strengthens barrier integrity by upregulating tight junction proteins in epithelial and endothelial cells. Building on Pete Batcheller’s hypothesis, maintaining sufficient blood levels of Vitamin D3 may help downregulate some of the upstream drivers of OSM expression while counteracting OSM’s disruptive effects on barrier function. Supporting this idea, work outside the headache field has shown that calcitriol can shift macrophages from an M1 pro-inflammatory state toward an M2 reparative state, reducing the production of OSM, TNF-α, and IL-6. A balanced view is important. The 2025 study identifies OSM as a persistent signal and points to specific differences between chronic and episodic CH. It did not identify a cause and it did not test interventions. The migraine-microbiome literature suggests dysbiosis as one possible upstream driver but translation to CH is yet to be explored. Other papers from this author on CH for your interest. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=Lund+NLT&cauthor_id=37667192 Includes an article titled "Current treatment options for cluster headache: limitations and the unmet need for better and specific treatments-a consensus article" which concludes "We find that there is a great and unmet need to pursue novel and targeted preventive modalities to suppress the horrific pain attacks for people with cluster headache."

-

- 4

-

-

Psilocybin Reduces Symptoms, Disability in Major Depression

Bejeeber replied to jon019's topic in Research & Scientific News

Hi @philiph, Magic mushrooms Busting dosage: typically in the .5g to 1.5g (dry) range. Reactions: Tripping, during the bust, then often relief from CH following, but also brace for possible 'slapbacks' (increased CH activity for a day or two). How long it takes varies, with 3 busting doses spaced 5 days apart an often successful protocol (for episodics anyway). It works for an impressively high percentage of us, but not 100% of us. DBS anecdote: One chronic member here had the DBS with no success, then eventually tried the mushrooms and got some very significant, sustained relief. The Blue 'NEW USERS - PLEASE READ HERE FIRST' banner at the top of the page links to more busting info. -

Psilocybin Reduces Symptoms, Disability in Major Depression

philiph replied to jon019's topic in Research & Scientific News

Hi, What experiences have people had with magic mushrooms (which is a class A drug - very illegal here in the UK). Dosage, reactions ,how long did it take to change the severity and pattern of the pain ? Is there any indication that it might work for some and not others. I have had 20 different prescribed drugs over 24 years, the last 15 off work. I have had oxygen, ONS and DBS surgery and it is still debilitating for several hours a day. It has been observed with MRI that my trigeminal nerve is half the diameter than it should be at the base of the brain. Anyone have anything similar ? Thank you for reading this, most are asleep at this stage. Cheers Philip -

Thank you SO MUCH.

-

I'm attaching a pic to illustrate parts of the regulator. When you turn the M tank on, the demand valve will be charged and ready to use. The mask flow control has no effect on the demand valve. You will leave it on "0" unless you use the O2 mask rather than the demand valve. You will need an adjustable wrench of sufficient size to attach the regulator to the tank and the demand valve to the regulator. Ensure the tank valve is closed before swapping regulators.

-

You are a life saver. I ordered this. I have checked is there any reference to how I connect my cluster mask, demand valve and this new regulator all together to tank. oxygen supplier is sending crap mask and 15lpm regulator so I want to be able assemble everything to use. I’m so desperate to get off so much Zembrace and start the oxygen. I’m getting killed in this cluster. 10 years I’ve had them and this is by far the worst. About 6 weeks now and they want send me DHE or Lithium next and I’m resistant to trying the lithium. Also about 5 days on D3 regimen

-

I think I have found a better deal for you. HERE This option will give you what you need plus a barb fitting for the mask as well so you can use either. Glad to help.

.thumb.png.076b827aa0cabf057a6e6525a4fce168.png)

.thumb.jpg.445b6e2a95d2dba3ca789ded86a496b4.jpg)

.thumb.png.73f9ba561402bcb5b70c18f4f5dfd61f.png)

.thumb.png.cec58e020ae25568c83382a412ee1c85.png)

.thumb.png.a3dec81d909a0d96fbdaf0f52d94f48a.png)

.thumb.png.0c2bad424ad5aa48bbce3ce7227362d3.png)

.thumb.png.d188ab319301fbb908d26ead456aeff9.png)

.thumb.png.a8d24c252cc92d37b2b1662e52d4cea3.png)

.thumb.png.a3cc69db9a06a2b1177860efee95cd88.png)

.thumb.png.f95b30446ff53863045ef9ad8a47dda1.png)

.thumb.jpg.24dde7ef3152d6d31b9546e3fec3b26d.jpg)